Taz: I’m here with with Lauren Ziel. I’m excited about getting to know you better, Lauren. I guess to start with…what does humanness mean to you?

Lauren: You know, when I think of humanness, I think of this idea of this eternal hope mixed with a lot of fallibility. A lot of pain, a lot of suffering, a lot of this capacity to self-preserve. And there’s a lot of ways that we self-preserve. Sometimes they benefit us at one point in our lives and then they no longer benefit us later on. The human condition is the depths and dark and deeply troubling things we can experience combined with this ability to overcome...maybe with a little help sometimes to overcome.

There’s this joke, and I don’t know if you’ve heard it. But when you’re in school, maybe undergraduate or in your master’s level work or so on, where the joke is that therapists are all crazy, and they’re taking these classes to figure out themselves and to figure out their experiences. And I think there is some truth to that. I think that our inherent curiosity about ourselves and how our brain ticks, how our heart beats, all of that definitely plays into…at least, I’ve used it as a way to connect to other people.

T: Your point about…this…well, I think of it as this Wounded Healer. Because of my background that I have…we talk about archetypes. This archetype of the Wounded Healer. And how we use our deepest wounds to be compassionate; to feel into what maybe the people we’re working with are feeling.

L: Absolutely. What I think is so great about this project is, you know, we are not this all-knowing entity sitting across the room from you. There’s a lot that I don’t about you - the person sitting across from me - and there’s a lot I’m still learning about myself, this world and my place in it, your place in it, and how we’re coming together in this room in this weird situation where it seems kinda contrived, but it’s really, potentially a vehicle and a space for tremendous vulnerability, but also safeness in that vulnerability.

There’s a strange way in working with my clients that make me feel accountable; that make me remember how much work it takes to figure out yourself. And it’s a motivation for me, honestly. Yeah, I think that’s the really cool part about doing what we do, or being in profession where you’re helping people on such a visceral level, on an emotional level…is it changes you. You learn so much.

T: Yeah, you’re speaking to how it can be transformative for you as the therapist…that you’re being impacted in some way by sitting with this person or working with them. Yeah, that it feeds something in you, not in a way that is impeding the work…but it’s…I’m forgetting the quote…something that Carl Jung says that it’s alchemical. That the two people are in are this space and they’re both gonna be transformed somehow. It’s not just about the client changing. I really like that, and that seems to be what you’re speaking about.

L: Yeah. Absolutely. I feel like I need to find the quote now, but yeah (laughs), absolutely. I think that the more I can bring myself to the table - my humanness, my fallibility, in a mindful and constructive manner - but the more that I can show up being a human...being…like I don’t know sometimes. I’ll tell you when I don’t know. I might feel a little silly and wish I that actually did know the answer. I want, in way to model, to model the vulnerability, and model it so that it’s okay.

T: You’ve talked a lot, I think, about how humanness shows up in your work as a therapist. I want to talk more about what you chose as your passion that represents your humanness. Even the phrase that you chose “movement is medicine” — I thought that it would be “fitness.” Say more about this idea of movement is medicine, and how it’s meaningful to you.

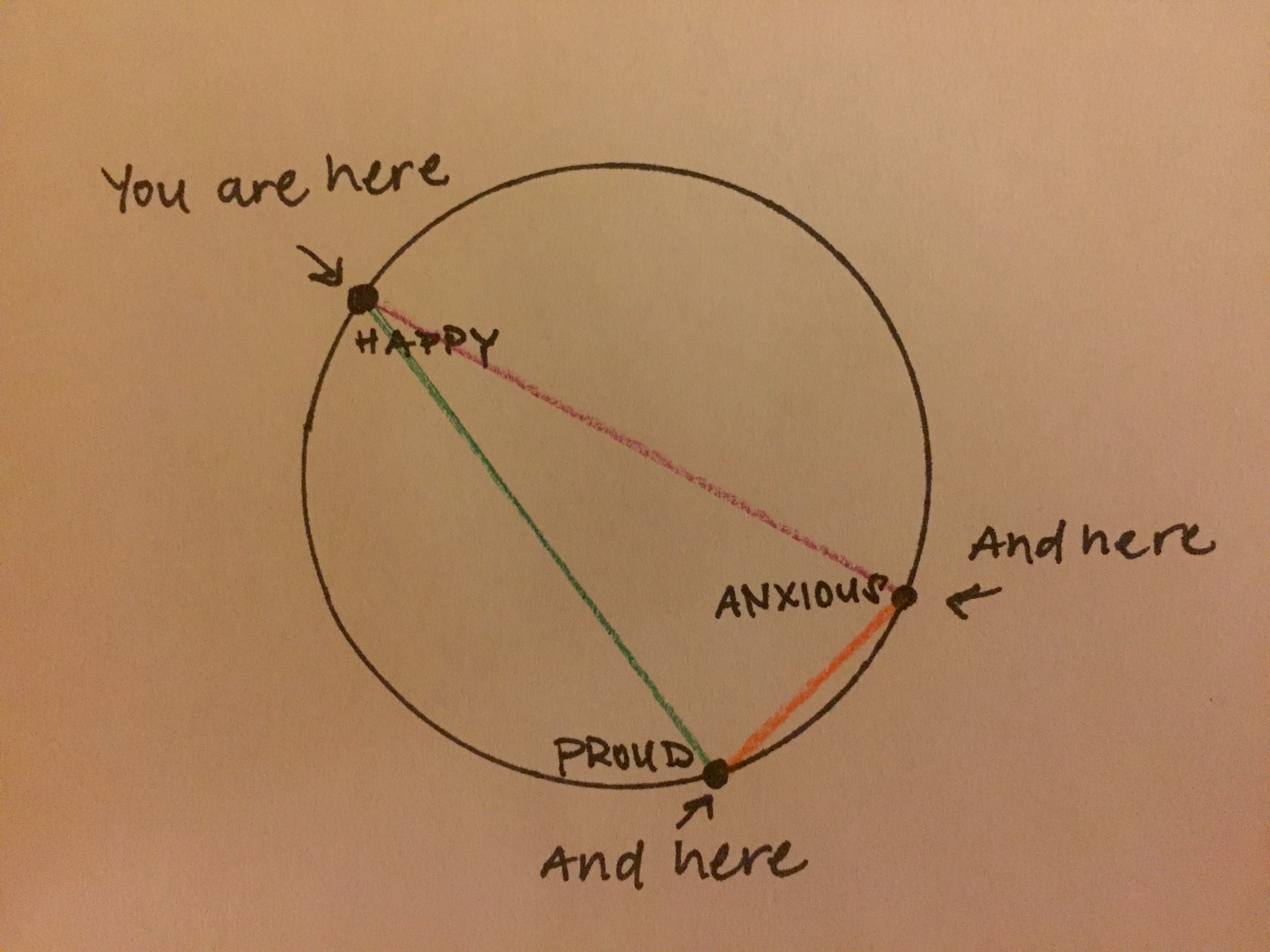

L: I think I have to start that with my own experience...in that, when I physically move, when I exert myself, when my heart rate is up, my respiration is up. Again this is how I do it. Some people would hate doing that, and I get it. When I’m sweating and exerting, and I’m fully engaged in what my body is doing in that moment….and I can feel the strike of my foot against the concrete… when I can feel how I roll my fingers over a dumbbell or a barbell as I move it - it’s really, honestly, a practice of mindfulness for me. It’s a practice of being in the present moment. There’s a degree of like a flow state where it almost just happening and there’s not a lot of thinking about. It parallels with this incredible attunement with your physical being. And it’s very grounding for me. It allows me to take my energy…because I can tend to be very heady and all up in my head and very light — pretty anxious. And using my body to ground me is very effective for me. It calms me down. It provides my brain with a little bit of clarity and being in that moment.